Some years ago, I divided my harvest of Red Pontiacs into two batches: one I cured, and one I didn’t. By January, nearly half of the uncured batch showed signs of rot, while only a handful of the cured potatoes were affected. Here’s why you should cure potatoes before you store them for winter.

Does this mean that curing is a must for storing potatoes before winter? At that time I thought not! But now I say it is. Successful potato storage starts with proper curing.

However many homesteaders rush their harvest straight into storage, cutting their potatoes’ shelf life in half, and should stop. If you haven’t tried that yet, here’s why you should:

Prevents Rot and Mold

Freshly dug potatoes bruise easily and get minor skin damage during harvesting. These small cuts, if untreated, let mold and rot sneak in.

That’s where curing comes in. It starts a natural healing process that seals these little wounds.

Over two weeks, the potatoes grow thicker skins. This new layer works like a shield, blocking bacteria and fungi. It cuts down the risk of rot.

This layer, called suberin, hardens the skin. It acts like a bandage and keeps the potatoes safe during storage.

Extends Shelf Life

Have you ever wondered how long do potatoes last if cured? Curing potatoes the right way helps them last much longer in storage than uncured ones. It’s a key step for keeping your crop stable and long-lasting.

When you let potatoes cure before storing, you give them a better chance at a longer shelf life. I’ve seen cured potatoes stay good for up to six months longer than uncured ones. Skipping this step can really cut into their storage time.

For many homesteaders, this makes a big difference. A fall harvest can stretch into March or April. That’s a lifesaver when fresh produce gets harder to find.

⇒ Why the Amish Store Their Potatoes In Sand

Maintains Flavor and Quality

Curing potatoes offers more than just longer storage; it also keeps their flavor intact. Right after harvest, their starches are still changing. Without curing, this process continues unevenly during storage.

Curing gives the potatoes time to balance their starch-to-sugar ratio. This balance is what makes them taste great and cook well. Uncured potatoes can develop an odd, overly sweet flavor. Sometimes, they even take on an unpleasant taste that ruins dishes.

I’ve tested this myself. In blind taste tests with my family, cured potatoes always win. They taste fresher, even months after harvest.

Increases Disease Resistance During Storage

Diseases like silver scurf and soft rot often show up in long-term potato storage, especially in humid root cellars. These issues can ruin an entire harvest if you’re not careful.

Related: Plant These To Keep The Pests Away

Curing strengthens the potato’s natural defenses. It thickens the skin and creates a barrier that blocks these diseases. In my early years, I didn’t realize how important curing was. Because of that, I lost entire batches to soft rot.

Now, I cure every harvest for a few weeks. Since then, storage diseases have become rare. This added protection is a must for any homesteader trying to keep their food supply safe through winter.

Helps Prevent Moisture Loss

Freshly dug potatoes have delicate, thin skin that loses moisture quickly. However, when you cure them, the skin thickens. This stronger layer acts as a natural sealant.

The thicker skin helps lock in moisture, keeping the potatoes firm and plump. Without curing, the thin skin can’t prevent dehydration. As a result, the potatoes dry out fast, especially in dry winter storage.

For homesteaders, moisture retention is key. It means you can enjoy potatoes that stay as fresh in January as they were in October. After a few weeks, uncured potatoes wrinkle, while cured ones keep their shape and texture.

Long-Term Benefits of Retaining Moisture

After years of observation, I’ve noticed that cured potatoes keep their moisture much longer than uncured ones.

Over a six-month winter storage period, cured potatoes lose only 10-15% of their water weight. In contrast, uncured potatoes can lose up to 40% or more. This moisture loss affects the quality and usability of your potatoes. Dried-out potatoes often become rubbery and lose flavor.

For varieties like Red Norlands and Yukons that lose moisture more quickly, proper curing makes a big difference. It can mean having fresh potatoes in March instead of a shriveled, unusable batch by mid-winter.

Long-Term Results in Different Storage Environments

Over the years, I’ve seen the benefits of curing in both controlled root cellars and less-than-ideal basement storage. For example, in my cellar, cured Kennebecs lasted well into May, whereas my neighbor’s uncured batch in a similar setup didn’t make it past February.

This extension of shelf life is not only practical but also economical, saving homesteaders the expense of buying replacements in the later winter months.

Curing helps to maximize your harvest and guarantees that the hard work of planting, tending, and harvesting continues to benefit you long after the growing season ends.

Duration of the Curing Process

I’ve found that 14 days is the sweet spot for curing. I know potatoes are properly cured when their skin is tough and don’t rub off easily with my thumb. Small cuts on the surface should appear corky, forming a protective layer.

Additionally, the potatoes should feel slightly denser when I handle them, indicating they are ready for storage.

Common Mistakes to Avoid During Curing

Over the years, I’ve made (and learned from) every possible curing mistake. It’s important to avoid certain mistakes when curing potatoes. Never wash them before curing, as moisture can lead to rot. Keep the temperature below 65°F during the curing process; I learned this the hard way when an entire batch spoiled.

Related: Strange Ways to Grow Potatoes In a Tiny Space

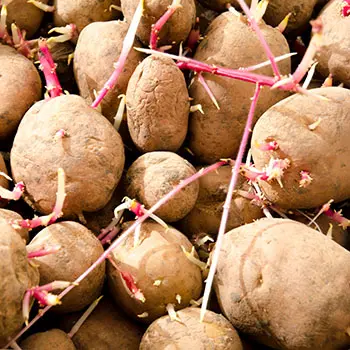

Avoid exposing the potatoes to direct sunlight, which can cause greening and sprouting. Don’t stack them more than two layers deep, as this restricts airflow and increases the risk of rot. Finally, never cure damaged potatoes, as they can quickly spread rot to the healthy ones.

Quality and Texture Differences in Cooking

Cured potatoes maintain a firm texture that holds up well in cooking, whether you’re making mashed potatoes, roasting, or frying.

Uncured potatoes, on the other hand, tend to develop a softer, less appetizing texture over time, which affects the quality of your meals.

I remember the difference vividly from one year when we stored uncured Russets. They turned into a sticky, overly soft mash rather than the light and fluffy texture we preferred.

The cured potatoes retained their ideal consistency, making them much more enjoyable to cook with and eat.

Personal Results of Implementing Curing

Before curing, storage diseases were responsible for nearly a quarter of my winter potato losses. Now, that figure has dropped to just a few percent each season.

By properly curing potatoes, I ensure that my harvest isn’t just stored—it’s protected. If you’re managing your winter food supply, this resistance to disease will provide you peace of mind and confidence that your stored food will last through to spring.

Why Not Start Curing

Proper curing is the single most important factor in successful long-term storage. The extra two weeks spent curing pays off enormously in reduced waste and better quality potatoes throughout winter.

My storage records show that since implementing these curing techniques, I’ve increased my useful storage time from 3-4 months to 6-8 months, effectively doubling the value of each harvest.

If you’re serious about food self-sufficiency, proper potato curing isn’t optional – it’s essential. These techniques work regardless of your scale – whether you’re storing 20 pounds or 200.

The key is attention to detail and patience during the curing process. Your reward will be months of home-grown potatoes that taste just as good in March as they did in September.

How To Grow An Endless Supply Of Potatoes

An Ingenious Eggshell Remedy and 25 Others Made from Things People Usually Throw Away (Video)

20+ Must-Have Seeds For The Upcoming Crisis

Household Items People Repurposed During the Great Depression

If they can’t be cured in sunlight how do you cure them? on plastic under shade trees? Need more info. I stopped growig them because my hubs never liked hilling them. Maybe the bags can help with this… Or I can put the Hubs in the compost, he undoes a lot of what I do and wrecks things.

If they can’t be cured in sunlight how do you cure them? on plastic under shade trees? Need more info. I stopped growig them because my hubs never liked hilling them. Maybe the bags can help with this… Or I can put the Hubs in the compost, he undoes a lot of what I do and wrecks things.